Tales of the Dark Age (No. 46)

By Zahra Hussaini, Translated by Skekib Jaghori

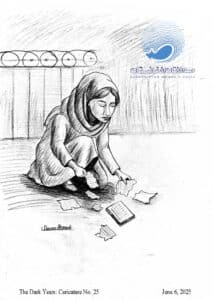

Her name is Mehrbanoo, a name that closely echoes her essence. She is a young woman of average height, with deep black eyes and hands that seem destined to paint. She has big dreams—vast, like a city with towering walls, reaching far beyond the limits of what most girls in Afghanistan dare to imagine. They are not just aspirations but a world of possibility, rising high against the horizon of a place where hope often feels out of reach.

Mehrbanoo finds herself in a world where color often fades into the background. She explains, “When I enter my small studio—once part of a renowned art school in northern Afghanistan—I am immediately surrounded by the beauty of colors. But the moment I step outside, the world turns gray and bleak. There are no girls in bright floral dresses, no laughter echoing through the streets. Everyone seems lost in the struggle to survive, rushing to earn their daily bread. Yet, I keep creating. Even in adversity, I continue to make art.”

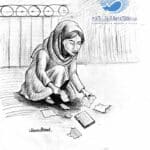

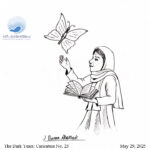

Life, she says, has lost much of its vibrancy since the Taliban’s return. She finds solace in her paintings, immersing herself in creativity. Even if only in her imagination, she breathes life into her art, creating a world far more colorful and alive than the reality that surrounds her. Despite the strict restrictions on women, Mehrbanoo has not given up. She rents a modest studio where she teaches painting to girls who can no longer attend school. Some of her former students have become teachers, passing on what they’ve learned. These art lessons keep them connected to beauty and expression, and provide a modest income—just enough for a piece of fabric, a bag, or a pair of shoes.

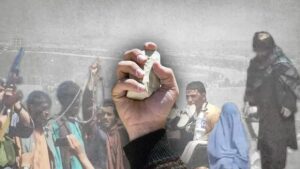

“Life has become much more difficult,” she says. “During the Republic, my art school was vibrant and full of life. But since the Taliban returned—along with the growing poverty and widespread fear—many of my students have stopped coming.”

She used to paint murals to supplement her income and worked on personal pieces at home. Back then, she had a reliable source of livelihood. Now that opportunity is gone.

“At night, when I lie down to sleep, I think about how much my family depends on me. If the Taliban shut down my small studio, all my dreams would collapse. This fear has haunted me ever since they came back.”

In the quiet of her gallery, surrounded by bursts of color on stark white walls, she feels momentarily alive, as if the vibrancy of the paintings could breathe life back into her. In her mind, she imagines herself laughing freely, her joy echoing beyond the canvas, defying the silence that blankets the streets. But then, a jar of paint slips from her hand. The sound of it hitting the floor snaps her back, and the illusion dissolves. The colors fade, and she is once again a woman living under the suffocating shadow of the Taliban.

“Every morning, I wake up with a fragile thread of hope. I get ready, put on my black hijab, and head to my studio. This dark veil feels especially heavy for someone like me—someone who lives with and breathes color. I often wonder what it would feel like to wear bright yellow, vibrant red, or rich green instead.”

Throughout the day, she lives in constant fear. The roar of a motorcycle or the raised voices outside make her heart race. She’s always worried that the Taliban might appear without warning and shut everything down.

“Being an artist in Afghanistan is incredibly difficult, especially for women. The challenges are even greater for those of us who rely on our art to express ourselves and survive.”

Finally, her voice—frail but resolute—breaks the silence. “I live through my art, through my paintings. If my voice is silenced and my art is extinguished, it will be as if I no longer exist,” says Mehrbanoo.