Tales of the Dark Age (No 3)

By Khaksha Qawmshahi, Translated by Laila Faizi

Raihana was a slim, thin, and polite girl from the Hazara community of Ghazni. For some time, she had been renting a room in the apartment unit across from mine—alone and on her own. Occasionally, she would knock on my door asking for tea, saffron, or kitchen supplies. She was a student at one of Kabul’s higher education institutions and was working on her thesis during those days. Most of the time, an IV cannula was taped to her hand, as if she suffered from anemia. She mentioned that her home was in Barchi, where she had her father, mother, brother, and family. Here, at Pul-e-Surkh intersection, she rented a room to be closer to the university.

It was during the final days before the fall of the government, amidst the Doha negotiations, the U.S.-Taliban agreement, and the successive collapse of provinces and districts. Every time I saw her, her mind seemed overwhelmed with terrifying questions, as though she was waiting for my return from the office. Perhaps she believed that my office was a source of answers to her questions. She would always ask, “Will the Taliban come?” “They say the Taliban flog and kill women.” Her face would then darken, her eyes searching invisible corners as she continued: “Will the Taliban take Afghanistan again?” “Will the Taliban kill Hazaras again?” “Will the Taliban stone women again?” “What will happen to my studies if the Taliban return? ”

The afternoon before the collapse, I returned to the apartment. She knocked on my door, her face was pale and yellow. In a trembling voice, she said, “I was a child when 23 years ago the Taliban took Afghanistan. I wish I had died back then.” Her gaze wandered far away, as though flipping through the pages of modern history. It seems that his thoughts took him back to August 8, 1998—the day when the Taliban killed at least 8,000 Hazara civilians in the Saidabad area of Mazar-e-Sharif. Blood seemed to splash before Raihana’s eyes. Eight thousand people, mostly civilians, were killed in a single day. Her gaze followed the spirits of the dead as though tracing a red line stretching from Mazar to Kabul. That red line extended further, to Yakawlang in Bamyan, where the Taliban massacred civilians on January 7th and 8th of 2001. They killed at least 278 people, 275 of whom were civilians.

With sorrow etched on her face, she said, “I’m scared, I’m trembling. I’m so terrified that I can’t even get to Dasht-e-Barchi.” Lost in her troubled thoughts, she asked, “How do the Taliban kill people? With guns? With whips and lashes? How?”

On the morning of August 15, 2021, I was sitting in my office at the Presidential Palace. The day before, the president had ordered that no one should be absent. He assured us that the Taliban would not reach Kabul’s gates. But I had a bad feeling. Around 9 a.m., chaos began. Anxiety filled the air. Rumors spread: “Gunfire has been heard on Kabul’s outskirts.” Suddenly, panic escalated. A devastating piece of news shook the walls: “Ashraf Ghani has fled.”

I rushed out of the office in confusion. Everyone was running and disappearing through doorways. As I exited, I saw flames in one corner—employees were burning human resources documents to prevent them from falling into the Taliban’s hands and exposing individuals. The city was in chaos, and people were running in every direction. After hours of chaos and turmoil, I finally made it back to my apartment. The streets and alleys seemed to tremble in fear of the Taliban’s arrival. It felt as if they were coming to slaughter everyone, just as they had done between 1996-2001.

The sound of my key turning in the apartment door seemed to be what Raihana had been waiting for all day. When I reached the second floor, her door was slightly ajar. With tired and anxious eyes, she peeked through the gap, looking at the staircase. Her eyes seemed to count each step I took toward her door.

When she saw me, some of her worries seemed to fade. “Have the Taliban arrived?” she asked with concern. “I…” Her voice broke into sobs. My anxious face seemed to have added to her despair. I said, “Yes, they have come.” My sorrowful tone frightened her. Her cries echoed through the apartment. I leaned against the wall by her door. And for a moment I was feeling the barrel of a gun pressing on my temple and picturing the scene of Taliban’s whipping this female student.

She sobbingly asked, “How will I get to Barchi?” Her trembling voice was showing the extent of her fears. As if the Taliban had come to stone every girl and woman, just as they had done before.

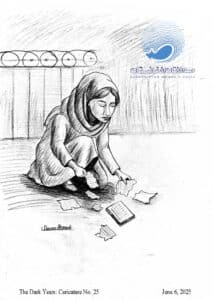

Time passed slowly. Every tick of the clock seemed to announce the Taliban’s arrival. Raihana was lost in her grief, and I was consumed by fears for my life. She gestured toward her appearance—her hair fell over her trembling shoulders. “I wish I had a Chador or scarf to get to Dasht-e-Barchi,” she said. Then she added, “Don’t you have a piece of black cloth I could use as a veil?”

Then she turned toward her room, a room that seemed to be in absolute chaos. Her eyes scanned her wardrobe, her hanging clothes, her scattered books, and her silent laptop. My gaze followed hers. It felt as though each hanging garment represented a woman whom the Taliban had hung from the gallows. Amid these thoughts, my mind raced to find something—a curtain, a sack, a sheet—that Raihana could use to cover herself and reach her home.

I checked the time. It was near sunset. Everything felt vague and confusing. Since leaving the office, all phone lines have been cut off. The internet wasn’t working. It seemed as if Kabul had been stripped of its soul with the Taliban’s arrival. In my frantic search for a solution, nothing came to mind to help Raihana.

I went to my room. Everything felt like a nightmare. I thought to myself, “Will I survive?” Everything seemed uncertain. The only clear reality was that the Taliban had returned, with their interpretation of Sharia law, ready to lash women, shave men’s heads, and punish them for not growing beard. They had come to turn Afghanistan into a slaughterhouse, and massacre ethnic and religious minorities. History was repeating itself. The U.S., with its agreement with the Taliban, and Ashraf Ghani had sacrificed democracy. Two things were clear: Ashraf Ghani had fled, and the Taliban, had seized power. Everything else was vague.

The only clear thing is that, at this moment, there are at least two criminals present in this apartment: me, a Hazara and a government employee, and Reyhaneh, a Hazara girl—free and democratic—with her liberal attire, who, in the constraint of a day like this, is searching for a piece of black fabric to wrap herself in so she can reach Dashte Barchi.

Finally, I escaped the country. But what happened to Raihana remains a mystery. Did she find a piece of cloth to wear the Taliban’s version of Islamic hijab? Did she die in her room from shock? Did she make it to Dasht-e-Barchi? These questions remain unanswered. All I know is that Raihana couldn’t contact her family in Dasht-e-Barchi that day because all communication lines were down. Kabul was in turmoil. Once again, it had become the playground of a terrorist group that are enforcing their version of Islamic law, targeting minorities, women, and liberal people.

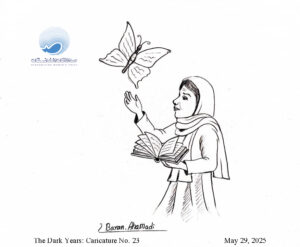

Where is Raihana now? Whatever the case, Raihana symbolizes millions of women and girls in my country—those who were erased from public life, work, freedom, education, and university by the Taliban’s return. My heart aches for Raihana. She has even been erased from life itself. Her thesis remains unfinished, and her seat at the university is gathering dust. I mourn for Raihana and the countless Raihanas of my homeland who burned in the Taliban’s fire, their ashes scattered by the winds of a bloodstained history. As I ponder my oppressed people’s fate, one question lingers in my mind: Will the smoke of this fire one day reach the eyes of these who ignited it?

This note was written in memory of Raihana, a girl as delicate as a basil leaf, who withered at the hands of the Taliban, and in remembrance of all the Raihanas of my land who are imprisoned by the Taliban or forced to leave their home and country.